By Karen Wells | CNA Media Team

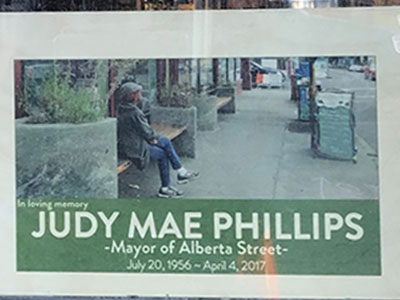

Taking photos in the neighborhood recently, two images got my attention. A photo of Judy Mae Phillips in the window of Alberta Cooperative Grocery and a “Black Mamas Matter” placard in another window nearby.

A Google search revealed a 2017 Oregon Public Broadcasting (OPB) story on the former.

Judy Mae “Pretty Eyes” was a 5-foot, 3-inch “tiny” woman, “a force of nature,” passionate about community with a beautiful singing voice.

She cared for her aging mother and older brother, helping with self-care, meals and daily routines.

When she wasn’t caregiving for family, she passed the time on the bench outside of Alberta Co-op, keeping an eye on life passing by. The bench was “her office,” a porch for her “day job.”

Judy Mae had a trusting familiarity with passersby, regardless of outward appearances. She was a cultural placeholder, a reminder of a way of life being replaced by a faster cadence.

She was the “eyes and ears” of the community. Judy Mae was woven into the cultural landscape, and she greeted volunteers and staff at Sabin Community Development Corporation, Alberta Co-Op and adjacent businesses.

Her purview included Otesha Place just across 15th Avenue. She knew the kids and parents.

Otesha Place is a mixed-use building with offices and affordable apartments. At the time of her passing in 2017, Judy Mae had progressed to first on the wait list for Otesha Place. She would’ve had a home of her own.

The OPB story used “panhandler” to describe her vocation while “at the office on the bench.” This description suggests Judy Mae was a “vagrant.” That’s the label used in the post-Civil War South for Blacks who couldn’t find work because of race codes of the era.

Judy Mae was a mother of three, a grandmother of 15. A symbol of “Black Mamas Matter,” she had a vocation and was always home by midnight to care for her mother and brother. She contributed to the social fabric of community.

Unfortunately “vagrant” hints at unintentional bias coloring her aura of humanity. Judy Mae was the embodiment of a neighborhood fading from the Alberta Arts District landscape.

What connects a photo in a storefront window and a placard in a neighbor’s? Humanity’s resilience. Do we celebrate an activist or pen a requiem for a neighborhood?

Thanks for asking.

Karen Wells is a semi-retired adult and early childhood educator. She serves on the planning committee of Womxn’s March and Rally for Action in Portland, WomxnsMarchPDX.com.