By Doug Decker | Historian

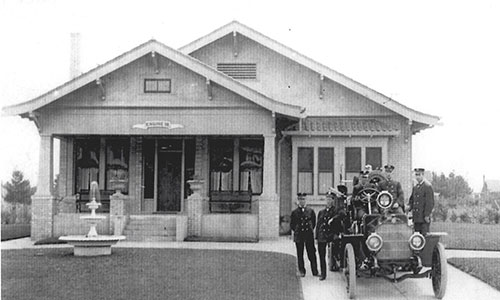

If someone asked you to find Foxchase on a map, could you? Here’s a clue: it was one of a dozen different subdivisions created more than 100 years ago which, taken together today, make up what we think of as the Concordia neighborhood. (For a visual clue, check out the 1954 photo on this page.)

Foxchase (not Fox Chase) was a subdivision platted in 1889 by J. Carroll McCaffrey that contains 15 square blocks, from Alberta to Killingsworth streets between 29th and 33rd avenues. Today, some might refer to the 30th-Killingsworth intersection as Foxchase, but it’s actually a much larger chunk of the neighborhood.

McCaffrey was a Georgetown-educated attorney, born and raised in Philadelphia, who kept a small practice there as well as here in Portland. He and wife Eugenie were busy on the social scene in both communities and frequent travelers back and forth.

Speculating in property was his specialty and he was getting ready for Portland’s boom times by buying up nearby open lands.

At that point in our history, there wasn’t much up here on these gentle slopes of the Columbia Slough and the Columbia River beyond. Fields, forests, a few dairies here and there, Homestead Act claims from the 1860s held by a couple dozen families.

Alberta was a dirt track meandering 10 blocks between what is now Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard (Union Avenue then) and what is today’s 15th Avenue.

McCaffrey sold lots in Foxchase and used that money to buy up other open land for the eventual grids of streets and lots that would follow.

Fox Chase is the name of a comfortable neighborhood in northeast Philadelphia, named for an 18th century inn. During McCaffrey’s timeframe of reference – the 1870s-1880s – Philadelphia’s rich and famous were building their mansions in Fox Chase. He and Eugenie were trying to call that to mind.

McCaffrey turned out to be a scoundrel who was arrested and imprisoned for land fraud. Homebuilding in the Foxchase plat didn’t really take off until after the turn of the century, years after his departure from Portland and his death.

But the name stuck and seems to be experiencing a bit of a renaissance at the moment. For more on McCaffrey and a look at the Foxchase plat, visit AlamedaHistory.org and enter “Foxchase” in the search box.

Doug Decker is taking a breather during the August and September CNews issues. But don’t let that discourage you from sending in questions about the history of the neighborhood and its buildings. Drop a line to CNewsEditor@ConcordiaPDX.org. CNews will save them for when Doug resumes and ask him to do some digging.

Doug Decker initiated his blog AlamedaHistory.org in 2007 to collect and share knowledge about the life of old houses, buildings and neighborhoods in northeast Portland. His basic notion is that insight to the past adds new meaning to the present.